Phoenix’s economy appears to be booming – but wages are failing to keep up, and prices are spiraling. How do voters see it?

In her back pocket, Ana Diaz carries a smooth grey pebble she calls her “knock-knocker”. She uses it to get a loud rap on the front doors of the South Phoenix neighborhood where she is canvassing for the Democrats ahead of November’s crucial midterm elections.

It’s 110F (43C) in the early afternoon sun, and Diaz is aiming to knock on 80 doors in this largely Latino neighborhood and speak to at least 20 people, encouraging them to vote. Diaz, a Los Angeles-based bartender and Unite Here union member, is a familiar face to many in this working-class area. In her T-shirt that reads “Worker power” she has been knocking on these doors since 2018.

Voters are all talking about the economy. Diaz, too, worries about inflation: her grocery bill is so high she thinks she may have to stop buying beef. But for her, the Democrats and good union jobs are the answer. “When we get together, we can make them change,” she says.

Joe Biden narrowly won Arizona in the 2020 election, beating Trump with 49.4% of the vote to Trump’s 49.1%. As in neighboring Nevada, campaigners like Diaz who got out the Latino vote were crucial to that victory. It’s going to take every vote this time too for the Democrats to hold the state – where a crucial Senate seat is up for grabs and with it control of Congress.

But Democrats enter election season with two major handicaps: the incumbent party historically loses seats in the midterms and the economy – the top issue for voters – is a mess.

For the first time since 1980, when Ronald Reagan defeated Jimmy Carter in a landslide, inflation is a major electoral issue. For decades the specter of inflation had seemed vanquished – hovering around 2% in the US. Now the shadow of soaring prices hangs over everything. In Phoenix, the inflation rate hit an annual rate of 13% in August, a record for any US city in data going back 20 years. The national average is 8.3%.

Phoenix maps all the contradictory signals the economy is sending. The city’s long economic boom continues. About 200 new residents have moved there every day in recent years, attracted by a lower cost of living and by businesses moving for less regulation and lower taxes. It’s not enough. The construction industry alone needs to add 265,000 qualified workers. Healthcare, financial services, all are struggling to fill vacancies.

This pressure-cooker environment has led to soaring rents in the city – up 46% over the year – but still lower than many other US cities. The situation is particularly hard for lower-wage workers and long-term residents now competing with more moneyed migrants from nearby California and elsewhere. For many, wages are failing to keep up with the cost of living crisis as inflation pushes up the price of everything from gas and food to construction costs.

“As cross-currents buffet the Arizona economy, it looks different depending on the lens used to view it,” University of Arizona professor George Hammond wrote in his latest report on the state of the state. Hammond is expecting slower growth in 2022 and 2023, which could help with costs but also cost people their jobs. Over the long term, he expects Arizona’s economy will still outpace the rest of the country.

Diaz believes the Democrats are best placed to navigate these strange seas. “People are like, ‘I really don’t care who gets in.’ But you should. Your streets need cleaning, you have no lights, your alleys are full of trash, we have a problem with homelessness. If we don’t choose the right people to make these changes, it’s not going to happen,” she says.

In Scottsdale, Phoenix’s affluent neighbor that is rapidly being absorbed by Phoenix’s sprawl, others have different views. “Biden is a nut,” says Jim Baumann, 60, shopping in Whole Foods in his orange Harley Davidson T-shirt. “He screwed this up.” His grocery bill now averages $300 to $350 a month he says, up from $200 before inflation bit. “I didn’t like Trump’s mouth, but he was better than Biden.”

Like so many other issues in the US, views on the economy are fractured, filtered by political and personal views and not always in line with today’s party doctrine.

Then there is abortion. Few decisions have greater economic consequences than the decision to have a child. In recent elections Republicans have paid the price for the supreme court’s decision to end the constitutional protection of abortion even in deep red states like Kansas. Last month an Arizona judge revived a highly restrictive law, that dates back to 1864, banning almost all abortions. Polls show the majority of Arizonans (Republicans and independents included) are in favor of keeping abortion legal in the state in most cases.

All this complexity is exacerbated by the weirding of the economy. “Strange would be an understatement,” says Greg Ayres, president of Corbins and chief operating officer of Nox Group, construction companies that specialise in water and waste management, data centers and work for the semiconductor industry.

Prices have soared for the construction industry, talent is in short supply, wages are rising and pandemic-related supply chain issues are still rippling through and causing delays. “Everything is so volatile,” he says. “Almost every project is over budget.” And yet business is good. His biggest immediate issue is finding enough people for all the projects he has on the go.

The company employs 750 people at present, up from 650 before the pandemic. He would like to be at 1,000 within the year. “But it’s really competitive.”

To attract workers, Corbin has upped its training programs, benefits and wages. Across the street from his office is a cavernous gym, recreation and health center with a full-time trainer on staff, added to attract and retain talent. Salaries are rising too. With overtime, Ayres says, a mid-20s journeyman, could make over $104,000 a year. The company will train up as many competent workers as it can get its hands on, he says.

The area is suffering from high inflation like the rest of the county but companies are still moving there in large numbers, he says. “By and large we are seeing an economy that is still very strong. It’s an interesting time.”

For some low-wage workers buffeted by these economic riptides “interesting” doesn’t even begin to describe it.

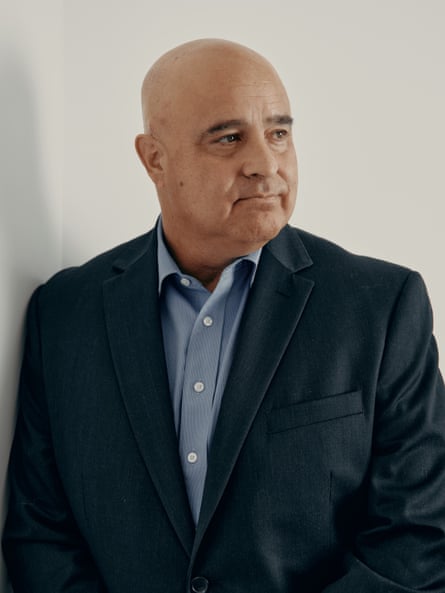

People know Jarvis Johnson in Phoenix. He went viral for his high-octane audition on reality show So You Think You Can Dance, and again for his dedication to Black Friday bargain shopping. His friends describe him as a “ball of energy” and an “eternal optimist”. But when I catch up with him between jobs he seems tired. It’s not surprising.

Johnson, 32, has been working three jobs to support his wife and his three young children. His day starts at 3.30am at a Covid testing center, and at 11am he starts his shift at a senior living center. Often he isn’t home before 8pm. He also puts in shifts at a local gas station, and is hoping to increase his hours there now that the Covid work is tapering off.

All of the jobs pay better than Arizona’s minimum wage of $12.80 an hour. The testing job paid $25 an hour during the worst of the pandemic, and at one point Johnson was working there 40 hours a week. But even then, his wages were barely keeping up with the cost of living.

Two years ago, when he moved into his apartment, he was paying $960 a month in rent. Now it’s close to $1,500. Gas prices have fallen in Arizona, as they have across the US, but are still about $4.90 a gallon, up from just over $3 a year ago. The couple have two cars and it costs $160 to fill them. Food is more expensive. His wife could go to work but daycare costs would wipe out her wages. “It’s crazy. Everything has got more expensive,” he says.

“It’s hard. It’s hard right now. I’m just trying to keep my head up and not let my kids see I’m struggling. I have to work my butt off to make it. I’m getting by, but it’s still not enough.”

Biden has promised a fairer, more equitable, economy. His administration passed the Inflation Reduction Act, which will increase taxes on the US’s largest companies and cut prescription drug prices. He’s also pouring money into solar energy and silicon chip production – both of which will benefit Arizonans. But will it be enough to persuade voters he really has a plan to steer them through this strange economic landscape?

Johnson says he will vote Democrat but he doesn’t believe either party has the solution. “They can’t do nothing for me. These employers, they need to pay their people,” he says. “People are struggling.”

He wants to start his own business – a hot-dog food truck. “I think I’d make more money working for myself, to be honest,” he says. At the moment he has about $1,000 saved, but it’s not enough and he’s worried that an incident, a broken car or worse, could wipe out his savings. “Anything can happen.”

In recent polls, American voters ranked “threats to democracy” as the most important issue facing the country. At a time of climate collapse, inflation and a pandemic, this is a remarkable statement on the fragility of America’s fundamental rights and freedoms.

The country is seeing a dizzying number of assaults on democracy, from draconian abortion bans to a record number of book bans. Politicians who spread lies and sought to delegitimize the 2020 election are pursuing offices that will put them in control of the country’s election machinery. Meanwhile, the supreme court is enforcing its own agenda on abortion, guns and environmental protections – often in opposition to public opinion.

With so much on the line, journalism that relentlessly reports the truth, uncovers injustice, and exposes misinformation is absolutely essential. We need your support to help us power it. Unlike many others, the Guardian has no shareholders and no billionaire owner. Just the determination and passion to deliver high-impact global reporting, always free from commercial or political influence. Reporting like this is vital for democracy, for fairness and to demand better from the powerful.

We provide all this for free, for everyone to read. We do this because we believe in information equality – that everyone needs access to truthful journalism about the events shaping our world, regardless of their ability to pay for it.

Every contribution, however big or small, powers our journalism and sustains our future. Support the Guardian from as little as $1 – it only takes a minute. If you can, please consider supporting us with a regular amount each month. Thank you.